Super Bowl LX: How Music Tells the American Story EN/FR

EN

Super Bowl LX: When Music Tells America’s Story

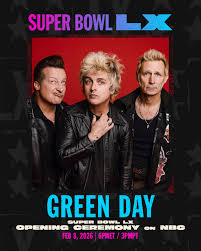

This Super Bowl unfolded in two crystal-clear acts: Green Day kicking off the game, followed by Bad Bunny headlining the halftime show.

Two musical worlds that seem miles apart on the surface, yet end up saying the same thing: music is never neutral, especially when it’s performed in front of the biggest audience on the planet.

FR

Super Bowl LX : quand la musique raconte l’Amérique

Ce Super Bowl s’est raconté en deux temps parfaitement lisibles : Green Day en ouverture du match, puis Bad Bunny au halftime.

Deux univers musicaux que tout oppose en apparence, mais qui racontent la même chose : la musique n’est jamais neutre, surtout quand elle s’exprime devant le plus grand public possible.

EN

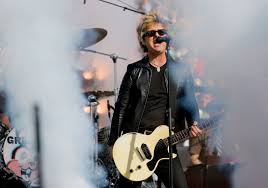

Green Day: Words First, Impact After

Green Day didn’t walk into the Super Bowl unarmed.

In the days leading up to the game, Billie Joe Armstrong spoke plainly, no hedging, no polish. Onstage, he confronted the crowd head-on, called people out, pushed buttons. That unfiltered line, if you work for ICE, quit your shitty job, wasn’t a slip or a stunt. It was a reminder: Green Day has always fused music and politics, anger and context. That reminder matters if you want to understand what comes next.

When the band opens the game, there isn’t a single word spoken. Instead: Holiday, Boulevard of Broken Dreams, American Idiot. Short songs, played fast, tight, stripped of any wasted air. The music takes over where the words left off—but it doesn’t erase them. And the energy hits instantly.

In the stands, it’s chaos in the best way. People jumping, screaming, singing louder than the PA. Tens of thousands of voices taking over the choruses. Punk didn’t mellow out, it relocated. It’s no longer coming from the singer’s mouth; it’s moving through the crowd’s bodies. Green Day plays locked in and electric, like everything could blow wide open at any second.

And that restraint, after what had been said in the days before, becomes a statement in itself. This silence isn’t surrender. It’s controlled tension. A way of saying that even inside the most tightly scripted, locked-down event in America, this music is still oppositional at its core.

Green Day doesn’t open the game to warm the crowd up. They open it to charge the atmosphere.

FR

Green Day : la parole lâchée avant, l’explosion pendant

Green Day n’arrive pas au Super Bowl désarmé.

Les jours précédents, Billie Joe Armstrong avait parlé sans détour. En concert, il avait interpellé le public frontalement, invectivé, provoqué. Cette phrase lancée sans filtre, si tu travailles pour l’ICE, démissionne de ton boulot de merde, n’était ni un dérapage ni une posture. C’était un rappel : Green Day est un groupe qui a toujours lié musique et politique, colère et contexte. Ce rappel est essentiel pour comprendre ce qui se passe ensuite.

Quand le groupe ouvre le match, plus un mot. À la place, Holiday, Boulevard of Broken Dreams, American Idiot. Des morceaux courts, joués vite, tendus, sans respiration inutile. La musique prend le relais de la parole, mais elle ne l’efface pas. Et surtout, l’énergie est immédiate.

Dans les gradins, l’ambiance est folle. Ça saute, ça hurle, ça chante plus fort que la scène. Les refrains sont repris par des dizaines de milliers de voix. Le punk ne s’est pas calmé : il s’est déplacé. Il n’est plus dans la bouche du chanteur, il est dans le corps du public. Green Day joue serré, électrique, comme si tout pouvait déborder à chaque instant.

Et cette retenue, après ce qui a été dit les jours précédents, devient en soi un message. Ce silence n’est pas une capitulation. C’est une tension assumée, une manière de rappeler que même dans le cadre le plus verrouillé du pays, cette musique reste une musique d’opposition.

Green Day n’ouvre pas le match pour faire monter la température. Ils l’ouvrent pour charger l’air.

EN

Bad Bunny: The Most-Watched Halftime Show Ever

When Bad Bunny hits the halftime stage, the scale shifts, hard.

This is no longer just a concert. It’s the most-watched halftime show in history, seen by more people than any other musical performance, anywhere. And the entire thing is in Spanish.

In a moment shaped by ICE raids, intensified crackdowns on immigrants, and political rhetoric openly hostile to Latino communities, that choice alone is a statement. Speaking Spanish here, now, in front of the entire country, is anything but accidental.

So when Donald Trump later calls the dancing “disgusting,” it’s not an artistic judgment. It’s a knee-jerk reaction. A rejection.

Because there are 62 million Spanish speakers in the United States. Because Spanish is an American language. And because this halftime show proves it, without asking for permission. Bad Bunny doesn’t respond to the controversy. He keeps going. He doubles down. He takes up space

Puerto Rico Front and Center, and an Identity Chosen by Name

Before getting into symbols, there’s one thing that needs to be said, and I’m saying it deliberately.

Bad Bunny’s real name is Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio. That’s not a biographical footnote. It’s not trivia. It’s a refusal of erasure. A way of reminding us that his identity doesn’t start with a globally palatable stage name, one that’s easily exported, smoothed out, and neutralized for the world market. Benito Martínez Ocasio is from Puerto Rico.

A U.S. territory with no presidential vote, no full political representation, trapped in a colonial status that has never truly been resolved. American when it’s convenient. Invisible when rights are on the line.

Saying his real name is a way of telling that story.

A personal story that is also a political one. An identity shaped by an island kept at the margins of a country that claims it without ever fully embracing it.

His 2025 album fits squarely into that arc: openly anti-colonial, blunt in how it addresses history, domination, and abandonment. Its impact goes far beyond music, to the point where it’s now studied in universities like Yale and UW–Madison in courses on the history of American colonialism.

This isn’t just pop anymore. It’s narrative. And it’s from that narrative that his halftime show draws its full meaning.

FR

Bad Bunny : le halftime le plus regardé de l’histoire!

Quand Bad Bunny arrive à la mi-temps, l’échelle change brutalement.

Ce n’est plus seulement un concert : c’est le halftime le plus regardé de l’histoire, un moment vu par plus de monde que n’importe quel autre spectacle musical. Et ce moment-là est entièrement en espagnol.

Dans un contexte de raids de l’ICE, de répression accrue contre les immigrés, de discours politiques ouvertement hostiles aux populations latino-américaines, ce simple fait est déjà une prise de position. Parler espagnol ici, maintenant, devant tout le monde, n’est pas anodin.

Quand Donald Trump dira plus tard avoir trouvé la danse « dégoûtante », ce n’est pas une critique artistique. C’est un réflexe de rejet.

Parce qu’il y a 62 millions d’hispanophones aux États-Unis. Parce que cette langue est américaine. Et parce que ce halftime le prouve sans demander l’autorisation. Bad Bunny ne répond pas à la polémique. Il continue. Il insiste. Il occupe.

Porto Rico au centre, et une identité qu’on choisit de nommer

Avant même d’entrer dans les symboles, il faut rappeler une chose, et je tiens à le faire ici.

Bad Bunny s’appelle Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio. Ce n’est pas un détail biographique. Ce n’est pas de l’érudition gratuite. C’est une manière, pour moi, de refuser l’effacement. De rappeler que son identité ne commence pas par un pseudonyme globalement digeste, exportable, neutralisé pour le marché mondial. Benito Martínez Ocasio vient de Porto Rico.

Un territoire américain sans droit de vote présidentiel, sans représentation pleine, coincé dans un statut colonial jamais vraiment réglé. Américain quand ça arrange, invisible quand il s’agit de droits.

Rappeler son vrai nom, c’est rappeler cette histoire-là.

Une histoire personnelle qui est aussi une histoire politique. Une identité façonnée par une île placée à la périphérie d’un pays qui la revendique sans jamais vraiment l’intégrer.

Son album sorti en 2025 s’inscrit d’ailleurs clairement dans cette continuité : ouvertement anticolonial, frontal dans sa manière de parler d’histoire, de domination, d’abandon. Un travail dont l’impact dépasse largement la musique, au point d’être aujourd’hui étudié dans des universités comme Yale ou UW–Madison dans des cours consacrés à l’histoire du colonialisme américain.

Ce n’est plus seulement de la pop. C’est un récit. Et c’est depuis ce récit-là que son halftime prend tout son sens.

EN

Showing, Not Preaching

Bad Bunny never raises his voice. He shows.

Everything points to Puerto Rico, without ever slipping into postcard imagery.

Sugarcane. Everyday scenes. References to the diaspora. And above all, that striking image: power poles with technicians hanging in midair, frozen in effort. It’s impossible not to read it as a blunt reminder of Puerto Rico’s energy crisis, made worse by Hurricane Maria and the political neglect that followed.

The shrubs taking over the stage aren’t random set dressing. They’re people. Human bodies hidden in plain sight, blended into the landscape. A clear metaphor for invisibility, for those society prefers not to see, even though they’re right there.

Even his outfit speaks. The name Ocasio. The number 64. An open-ended number, layered with meaning: family memory, political history, sports, Puerto Rican identity folded into the American narrative. Nothing is fixed, and that ambiguity is exactly what gives the symbol its power.

Bad Bunny explains nothing. He lets the connection happen.

Simple Gestures on a Massive Stage

In the middle of this enormous production, Bad Bunny chooses intimacy. He celebrates a real wedding on the field. No irony. No wink to the camera. A real couple, real vows, love made public in front of the entire world.

Then comes the suspended moment:

Bad Bunny hands his Grammy Award of the Year to a child. A trophy just won, passed on like a glimpse of a possible future. The gesture is simple, but at this scale, it becomes monumental. It speaks to transmission, legitimacy, inheritance.

At that exact moment, the boy is watching, on a TV screen, Bad Bunny’s Grammy Awards speech, the one where he took a stand against ICE. In other words, what’s being passed on isn’t just a trophy. It’s a voice. A memory. A political and cultural through line. The award doesn’t fall from the sky, it comes from a fight, from a position clearly taken.

FR

Montrer plutôt que dénoncer

Bad Bunny ne crie jamais. Il montre.

Tout parle de Porto Rico, sans jamais tomber dans la carte postale.

La canne à sucre. Les scènes de vie quotidienne. Les références à la diaspora. Et surtout cette image forte : les poteaux électriques, avec des techniciens suspendus dans le vide, figés dans l’effort. Impossible de ne pas y lire un rappel brutal de la crise énergétique de Porto Rico, aggravée par l’ouragan Maria et l’abandon politique qui a suivi.

Les arbustes qui envahissent la scène ne sont pas un décor absurde. Ce sont des gens. Des corps humains dissimulés, confondus avec le paysage. Une métaphore limpide de l’invisibilisation : celles et ceux qu’on préfère ne pas voir, mais qui sont bien là.

Même sa tenue devient langage. Le nom Ocasio. Le numéro 64. Un chiffre ouvert, chargé de couches : mémoire familiale, histoire politique, sport, identité portoricaine prise dans le récit américain. Rien n’est figé, et c’est précisément ce flou qui rend le symbole puissant.

Bad Bunny n’explique rien. Il laisse le lien se faire.

Des gestes simples, à une échelle démesurée

Au milieu de ce dispositif gigantesque, Bad Bunny choisit l’intime.

Il célèbre un vrai mariage sur la pelouse. Pas une mise en scène ironique. Un couple réel, une promesse échangée, l’amour rendu public devant le monde entier.

Puis vient ce moment suspendu :

Bad Bunny offre son Grammy Award de l’année à un enfant. Un trophée tout juste gagné, transmis comme on transmet un futur possible. Le geste est simple, mais à cette échelle, il devient immense. Il parle de transmission, de légitimité, d’héritage.

À ce moment précis, le petit garçon est en train de regarder, sur un écran de télévision, le discours de Bad Bunny aux Grammy Awards, celui dans lequel il prenait position contre l’ICE. Autrement dit, ce qui est transmis, ce n’est pas seulement un trophée. C’est une parole. Une mémoire. Une continuité politique et culturelle. Le prix ne tombe pas du ciel : il vient d’un combat, d’un positionnement assumé.

EN

A Community, Not a Showcase

The guests are never just window dressing.

Lady Gaga doesn’t show up to dominate the stage. She locks into the rhythm, the movement, the collective energy.

Ricky Martin carries memory, he’s a bridge between generations of Latino artists. And the song he performs isn’t a feel-good nostalgia hit. It’s a track about mass tourism and the gentrification of Puerto Rico. About an island turned into a backdrop, a commodity, a profitable destination, often at the expense of the people who still live there.

In the context of the Super Bowl, the most hyper-commercial event imaginable, that choice is anything but random. It plants a critique from the inside, soft on the surface, deeply political underneath.

Around them, Karol G, Cardi B, Pedro Pascal, and Jessica Alba form a shared space. Not a stack of celebrity cameos, but a visible community, gathered at the center of the most exposed spectacle on Earth.

The Final Balloon: Redefining America

At the end, a balloon rises.On it, a simple message: Together, we are America.

Then Bad Bunny names every country in the Americas. Not for aesthetics. Not to check a box. But to restate an obvious truth that some insist on denying: America isn’t just one country. It’s a continent. A shared history. Multiple languages. Interwoven cultures.

FR

Une communauté, pas une vitrine

Les invités ne sont jamais décoratifs.

Lady Gaga ne vient pas dominer la scène. Elle s’inscrit dans le rythme, la danse, l’énergie collective.

Ricky Martin incarne une mémoire, un passage de relais entre générations d’artistes latinos, d’ailleurs le morceau cqu’il chante n’est pas un simple tube nostalgique. C’est un titre qui parle du tourisme de masse et de la gentrification de Porto Rico. De l’île transformée en décor, en produit, en destination rentable, souvent au détriment de celles et ceux qui y vivent encore.

Dans le contexte d’un Super Bowl, événement ultra-commercial par excellence, ce choix n’a rien d’anodin. Il introduit une critique de l’intérieur, douce en apparence, mais profondément politique.

Autour d’eux, Karol G, Cardi B, Pedro Pascal, Jessica Alba composent une scène commune. Pas une addition de stars, mais une communauté visible, rassemblée au centre du spectacle le plus exposé du monde.

Le ballon final : redéfinir l’Amérique

À la fin, un ballon s’élève. Dessus, un message simple : ensemble, nous sommes l’Amérique.

Puis Bad Bunny énumère tous les pays du continent américain. Pas pour faire joli. Pas pour cocher une case. Pour rappeler une évidence que certains refusent : l’Amérique n’est pas qu’un pays. C’est un continent. Une histoire partagée. Des langues multiples. Des cultures entremêlées.

EN

Two Strategies, One Impact

Green Day strikes first, speaks loud, hits hard, then lets the music do the damage under tight constraints.

Bad Bunny never raises his voice, but turns halftime into a massive, precise cultural assertion, one that’s impossible to ignore.

Two opposing languages. The same result.

This Super Bowl didn’t try to be apolitical. It simply showed that music is political, even when it never says the word out loud. And when that many people are watching at the same time, when that many bodies are vibrating together, it inevitably becomes history.

I love Green Day. I love Bad Bunny. I love Lady Gaga. I hate the Patriots. So honestly, the Seahawks winning works just fine for me. Even as a Niners fan, losing to the champs is always the classier way to go.

FR

Deux stratégies, un même impact

Green Day attaque avant, parle fort, puis laisse la musique frapper sous contrainte.

Bad Bunny ne crie jamais, mais transforme la mi-temps en affirmation culturelle massive, précise, impossible à ignorer.

Deux langages opposés. Un même effet.

Ce Super Bowl n’a pas cherché à être apolitique. Il a simplement montré que la musique fait de la politique même quand elle n’en prononce pas le nom. Et quand autant de gens regardent en même temps, quand autant de corps vibrent ensemble, ça devient forcément historique.

J’aime Green Day, j’aime Bad Bunny, j’aime Lady Gaga, je déteste les Patriots, alors franchement, que les Seahawks gagnent, ça me va très bien. Même en tant que fan des Niners : perdre contre les champions, c’est toujours plus classe.

Explore our latest live reports and Behind The Stage articles!

Découvrez nos derniers live reports et nos articles Behind The Stage !